A recent study delved deep into the intricate ways in which sleep contributes to processing emotional memories, a fundamental aspect of maintaining good mental health. Drawing on more than twenty years of research, the study shed light on how neurotransmitters like serotonin and noradrenaline, which remain inactive during REM sleep, play a crucial role in recalibrating emotional experiences.

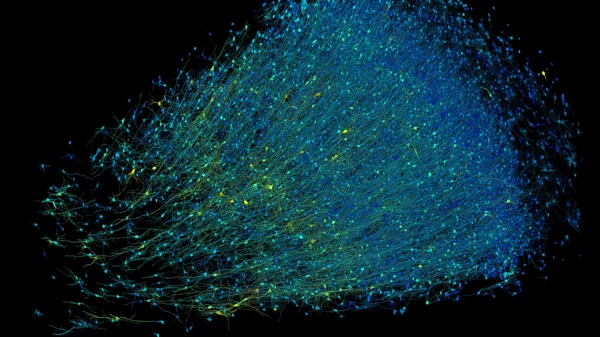

The research underscores the importance of two key brain regions, the hippocampus and the amygdala, in transforming newly acquired emotional memories into familiar ones, all without triggering the typical stress responses observed during wakefulness. These findings advocate for targeted interventions aimed at improving sleep quality to support emotional and mental well-being, particularly for individuals grappling with sleep disorders.

Led by Dr. Rick Wassing from Woolcock, an international team published their findings in Nature Reviews Neuroscience. Their extensive analysis not only reaffirms the age-old wisdom of a good night’s sleep for emotional balance but also delves deeper into the underlying mechanisms.

“We’ve gone beyond just saying sleep is important; we’ve delved into why,” explains Dr. Wassing, who spearheaded the two-year-long project. “By synthesizing research across neurobiology, neurochemistry, and clinical psychology, we’ve gained valuable insights into how sleep aids in processing emotional memories.”

The team’s amalgamation of scientific knowledge spanning two decades reveals the critical role of neurochemical regulation, particularly of serotonin and noradrenaline, during sleep. These neurotransmitters, pivotal in assessing and responding to emotional stimuli, are effectively silenced during REM sleep, providing an opportune window for the brain to engage in vital processing tasks.

According to Dr. Wassing, two primary mechanisms come into play during sleep to process emotional memories, both involving the hippocampus and the amygdala. While the hippocampus catalogs daily experiences, the amygdala, closely tied to emotional responses, triggers physical reactions like a racing heart or knots in the stomach during wakefulness.

During REM sleep, the brain revisits and reactivates these newly formed memories. However, with serotonin and noradrenaline systems offline, the brain can effectively move these memories from the “novelty” store to the “familiar” one without inducing the typical fight-or-flight response associated with emotional experiences.

In essence, this study underscores the intricate chemistry and circuitry at play during sleep, highlighting its pivotal role in emotional processing and long-term mental well-being.