Exciting news from the world of science! Researchers believe they’ve stumbled upon a hidden genetic trigger for Alzheimer’s disease. In a groundbreaking study released on Monday, they’ve uncovered strong evidence suggesting that individuals carrying two copies of a particular genetic variation linked to Alzheimer’s risk are highly likely to develop the neurodegenerative disorder as they age. This revelation challenges previous assumptions and could have significant implications for our understanding and treatment of the disease.

Alzheimer’s is a devastating form of dementia affecting millions of people worldwide, with around 7 million Americans currently battling the condition. While age, cardiovascular health, and genetics all play roles in its development, the discovery of this new genetic link sheds fresh light on the complexity of the disease.

Previously, scientists identified rare mutations that virtually guarantee the onset of Alzheimer’s at a younger age. However, there are also mutations, like the one affecting the apolipoprotein E gene (APOE), that increase the risk of the more common form of Alzheimer’s, typically seen in individuals over 65. One such mutation, known as APOE4, is carried by about a quarter of the population.

Until now, most studies treated individuals with one or two copies of the APOE4 gene as a single group. However, this new research suggests that those with two copies, referred to as APOE4 homozygotes, face a significantly higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

A collaborative effort between researchers from Spain and the U.S. analyzed data from various sources, including brain donor records and biomarker studies related to Alzheimer’s. Their study, which involved over 13,000 participants, revealed compelling findings.

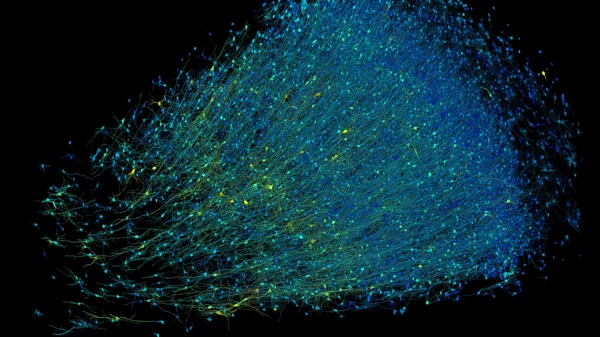

In brain donor data, nearly all individuals with two APOE4 genes exhibited significant brain changes associated with Alzheimer’s upon their passing. Conversely, only half of those with the most common APOE variant, APOE3, showed similar changes. Similarly, biomarker data indicated that almost all APOE4 homozygotes displayed abnormal levels of amyloid beta—a potential early indicator of Alzheimer’s—by age 65.

The study’s findings, published in Nature Medicine, suggest an almost-certain link between having two APOE4 copies and developing Alzheimer’s by midlife. This genetic mutation may represent a distinct, more common form of the disease.

The implications of these findings are profound. They could reshape how we approach Alzheimer’s research, leading to a more nuanced understanding of its genetic underpinnings and potentially paving the way for more effective treatments in the future.

Ultimately, this study underscores the importance of recognizing and addressing the diverse genetic factors contributing to Alzheimer’s. By doing so, we can better equip ourselves to tackle this debilitating disease and provide hope for those affected by it.