Researchers have just uncovered a significant breakthrough in understanding late-in-life Alzheimer’s disease—a genetic form linked to inheriting two copies of a particular gene.

The gene, APOE4, has long been recognized as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s, particularly as people age. However, new research suggests that for individuals with two copies of this gene, it moves beyond being just a risk factor to become an underlying cause of the disease.

This discovery, led by Dr. Juan Fortea of the Sant Pau Research Institute in Barcelona, Spain, carries profound implications. It indicates that symptoms of Alzheimer’s may appear seven to 10 years earlier in those who carry two copies of the APOE4 gene compared to other individuals who develop the disease later in life.

Roughly 15 percent of Alzheimer’s patients carry two copies of APOE4, highlighting the genetic basis of these cases. Prior to this research, genetic forms of Alzheimer’s were believed to primarily affect individuals at much younger ages, constituting less than 1 percent of all cases.

The identification of APOE4 as a causative factor underscores the urgency to develop treatments targeting this specific gene. Some medical professionals hesitate to prescribe the only drug known to modestly slow Alzheimer’s, Leqembi, to individuals with the gene pair due to an increased risk of dangerous side effects.

Dr. Reisa Sperling, a coauthor of the study at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, emphasizes the importance of targeting this high-risk group before symptoms emerge. However, she advises against widespread gene testing, noting that the APOE4 gene duo is not responsible for the majority of Alzheimer’s cases.

Genetics plays a crucial role in Alzheimer’s disease, with APOE4 being a significant genetic risk factor. While most cases of Alzheimer’s occur later in life, typically after the age of 65, the presence of two copies of the APOE4 gene can accelerate the onset of symptoms.

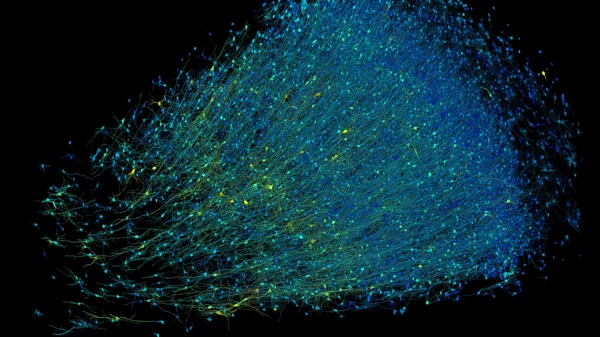

Fortea’s research team analyzed data from thousands of individuals and brain donations to elucidate the role of the APOE4 gene in Alzheimer’s. They found that individuals with two copies of APOE4 exhibited increased accumulation of amyloid plaques in the brain, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s, starting as early as age 55.

Despite these advancements, much remains unknown about why some individuals with two APOE4 genes do not develop Alzheimer’s symptoms. Further research is needed to uncover the underlying mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets associated with this genetic predisposition.

While the drug Leqembi shows promise in clearing amyloid plaques, its efficacy and safety in individuals with two APOE4 genes are uncertain due to the elevated risk of adverse effects. Future research may explore alternative treatments, such as gene therapy or drugs specifically targeting APOE4.

Overall, these findings have significant implications for Alzheimer’s research and treatment, highlighting the importance of genetic factors and the need for personalized approaches to manage the disease.