The familiar saying “The enemy of my enemy is my friend” isn’t just a cliché from cheesy movies or playground disputes. It actually stems from a psychological theory proposed by Fritz Heider in the 1940s, and now, it seems, science has backed it up.

A team of researchers from Northwestern University used physics and statistical theory to confirm Heider’s ideas. István Kovács, the senior author of the study, sheds light on the significance of “friends” and “enemies” and how their team reached the conclusion that Heider was onto something.

So, what’s this social balance theory all about?

At its core, the theory revolves around achieving cognitive consistency, which is a step towards psychological balance. People naturally seek harmony in their relationships, and when these relationships don’t align with the four rules outlined by Heider, it creates tension until they find a way to restore harmony by changing their feelings towards one of the elements involved.

For example, if you’re a fan of a celebrity who endorses a product you dislike, you’re left feeling conflicted until you reconcile your feelings about either the product or the celebrity. This brings back harmony.

As Kovács explains, “Social balance is about how people interact within a group, usually involving at least three people, forming a triangle. The connections between them represent the sentiment of their relationships, positive or negative.”

He elaborates, “Balance is achieved when all relationships are positive or when two negative relationships are balanced by one positive relationship. Any other scenario leads to unbalanced triangles, causing tension or frustration.”

But validating this theory has been tricky. Despite numerous attempts by researchers using network science and mathematics, they’ve often fallen short due to the complexities of real social networks, which rarely adhere to perfectly balanced relationships as proposed by the theory.

The breakthrough came when the team from Northwestern University managed to overcome this challenge by integrating two crucial components essential for Heider’s framework to work effectively: not everyone knows each other, and individuals vary in their positivity towards others.

While previous models could only accommodate one factor at a time, the researchers’ model incorporated both constraints simultaneously. This integration finally substantiated Heider’s theory nearly eight decades after its inception.

As Kovács points out, their interest in the subject was piqued by the 2021 Nobel Prize awarded to Giorgio Parisi, whose work on complex physical systems shares parallels with social dynamics.

He notes that just as competing interactions between spins can lead to configurations unable to minimize all pairwise interactions in physics, similar frustrations can arise in social systems due to conflicting interpersonal relationships or attitudes.

To delve into this further, Kovács’s team analyzed extensive signed network datasets from various social contexts. Their model departed from assigning purely random positive or negative values to the edges, instead incorporating statistical approaches to allocate values based on the likelihood of such interactions occurring in real-life scenarios.

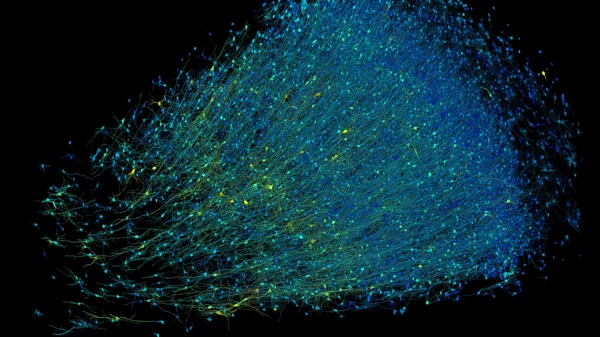

By integrating these two constraints, the resulting model consistently demonstrated alignment with Heider’s social balance theory across large-scale social networks, offering valuable insights into social dynamics, political polarization, international relations, and beyond.

Ultimately, this research sheds light on our behaviors and motivations in establishing social interactions, offering potential applications in diverse fields like neuroscience and pharmacology. As we continue to explore the intricacies of human networks, this theory provides a valuable framework for understanding social dynamics and fostering harmony in our interactions.